Earlier than historical Egyptians refined the Great Sphinx of Giza, pure forces could have helped carve the enduring monument’s huge feline form out of a single mass of limestone.

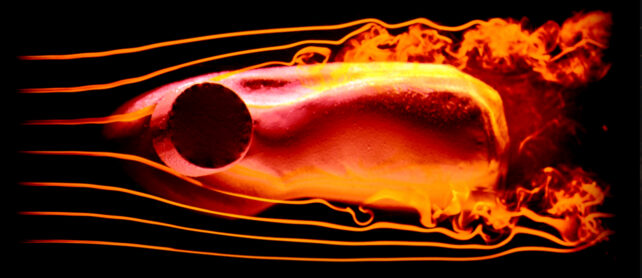

Fluid dynamics experiments reveal the construction’s ‘reclined lion’ form might have been carved not by human fingers, however fast-flowing wind.

“Our findings offer a possible ‘origin story’ for how Sphinx-like formations can come about from erosion,” says experimental physicist and utilized mathematician Leif Ristroph from New York College.

“Our laboratory experiments showed that surprisingly Sphinx-like shapes can, in fact, come from materials being eroded by fast flows.”

Hypothesis over nature’s hand in carving the Sphinx is not new. Way back to the Fifties, it has been advised the statue’s physique could have been weathered by ancient waters.

Whereas there’s ample proof to low cost the opportunity of rains or floods being accountable, different specialists have advised wind – although much less highly effective – could have scoured the general form out of the right combination of rocks.

This concept dates again to the early Nineteen Eighties, with a situation advised by a former NASA geologist named Farouk El-Baz.

“The ancient engineers may have elected to reshape its head in the image of their king,” wrote El-Baz in 2001. “They also gave it a convincingly lion-like body, inspired by forms they encountered in the desert. To do so, they had to dig a moat around the natural protrusion.”

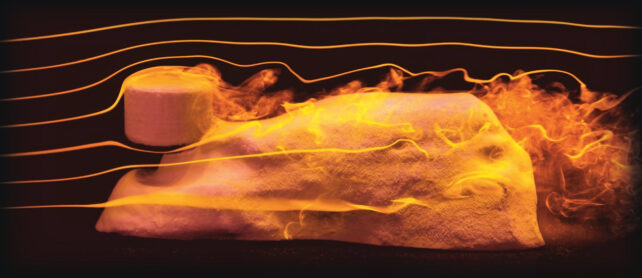

Ristroph and colleagues washed chunks of clay containing a combination of sentimental and onerous bits in fast-flowing streams of water to copy the wind’s drive to see what shapes would emerge.

They primarily based the water’s actions on circumstances within the space 4,500 years in the past (the Sphinx’s contentious age), and used dye to assist observe the dynamic flows across the eroding clay.

The ensuing shapes resemble yardangs, contorted hunks of stone seen in lots of desert areas the place winds scoop up sands to hurl at each impediment. Finally, this sandblasting can form even the toughest and most huge rock formations into convoluted buildings.

“There are, in fact, yardangs in existence today that look like seated or lying animals, lending support to our conclusions,” says Ristroph.

The irregular juts, nooks, curves, and textures of yardangs are designed by a mix of wind power, angle, and frequency, in addition to the composition of the stone: softer elements of the rock erode first leaving randomly formed more durable elements uncovered to divert the wind flows.

Within the Sphinx’s case, sooner flows had been funneled collectively by the more durable ‘head’ and ‘paws’ to hit the deepest carved prevailing-wind-facing a part of the limestone monolith – the ‘neck’ – earlier than the air streams cut up to circulate across the large cat shoulders.

“These compounding effects could explain the locally high shear stress and high erosion rate just under the head and hence why strong carving digs the neck and reveals the paws,” the researchers explain in their paper.

The Sphinx’s erosion continues today.

As El-Baz had beforehand pointed out, and not using a deep understanding and affect of nature the marvels which might be the Egyptian monuments wouldn’t have survived their harsh surroundings for lengthy.

“Had the ancients built their monuments in the shape of a cube, a rectangle, or even a stadium,” El-Baz noted, “they would have been erased by the ravages of wind erosion long ago.”

As an alternative, the spectacular construction nonetheless towers 20 meters (66 toes) excessive and about 73 meters lengthy, having far outlasted the knowledge of its intended meaning.

This analysis has been printed in Physical Review Fluids.