When Eric Mueller, who was adopted, first noticed {a photograph} of his delivery mom, he was overcome by how alike their faces had been. It was, he wrote, “the first time I ever saw someone who looked like me.” The expertise led Mueller, a photographer in Minneapolis, right into a three-year challenge to {photograph} a whole bunch of units of associated folks, culminating within the e-book Household Resemblance.

Such resemblances are commonplace, after all — they usually level to a powerful underlying genetic affect on the face. However the nearer scientists look into the genetics of facial options, the extra complicated the image will get. Tons of, if not 1000’s, of genes have an effect on the form of the face, in principally refined ways in which make it practically inconceivable to foretell an individual’s face from inspecting the affect of every gene in flip.

As researchers be taught extra, some are beginning to conclude that they should look elsewhere to develop an understanding of faces. “Maybe we’re chasing the wrong thing when we’re trying to create gene-level explanations,” says Benedikt Hallgrímsson, a developmental geneticist and evolutionary anthropologist on the College of Calgary, Canada.

As an alternative, Hallgrímsson and others suppose they are able to group genes into groups that work collectively because the face kinds. Understanding how these groups work, and the developmental processes they have an effect on, ought to be far more manageable than attempting to type out the consequences of a whole bunch of particular person genes. In the event that they’re proper, faces could become easier than we expect.

Plotting the facial panorama

When geneticists first got down to perceive faces, they began with the low-hanging fruit: figuring out the genes accountable for facial abnormalities. Within the Nineteen Nineties, for instance, they realized {that a} mutation in a single gene causes Crouzon syndrome — characterised by wide-set, usually bulging eyes and an underdeveloped higher jaw — whereas a mutation in a distinct gene results in the down-slanting eyes, small decrease jaw and cleft palate of Treacher Collins syndrome. It was a begin, however such excessive circumstances mentioned little about why regular faces differ as a lot as they do.

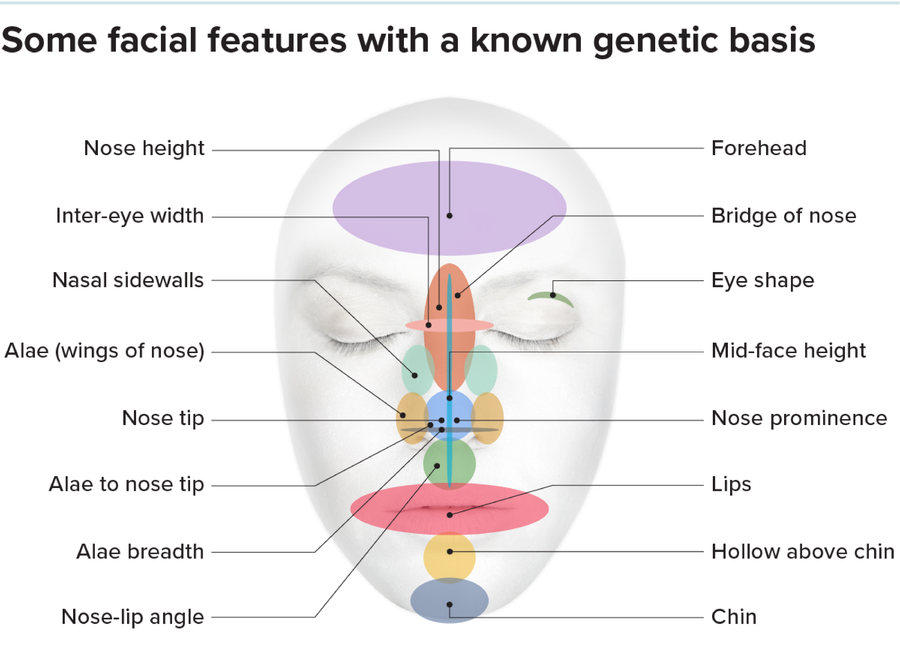

Then, starting a few decade in the past, geneticists started to take a distinct method. First, they quantified 1000’s of regular faces by figuring out landmarks on every individual’s face — tip of chin, corners of lips, tip of nostril, outdoors nook of every eye, and so forth — and measuring the distances between them. Then they screened the genomes of these people, to see whether or not any genetic variants corresponded with explicit facial measurements, an evaluation generally known as a genome-wide affiliation research, or GWAS (pronounced jee-wass).

Some 25 GWASs of facial form have been revealed to this point, with over 300 genes recognized in complete. “Every single region is explained by multiple genes,” says Seth Weinberg, a craniofacial geneticist on the College of Pittsburgh. “There’s some genes pushing outward and others pushing inward. It’s the total balance that ends up becoming you, and what you look like.”

Not solely are there a slew of genes concerned in every explicit facial area, the variants uncovered so far don’t account effectively for the specifics of every face. In a survey of the genetics of faces within the 2022 Annual Overview of Genomics and Human Genetics, Weinberg and his colleagues gathered GWAS outcomes on the faces of 4,680 folks of European ancestry. Identified genetic variants defined solely about 14 % of the variations in faces. A person’s age accounted for 7 %, intercourse for 12 %, and physique mass index for about 19 % of variation, leaving a whopping 48 % fully unexplained.

Clearly, one thing necessary in figuring out the form of faces isn’t captured by GWASs. After all, some portion of that lacking variation have to be defined by setting — actually, researchers have famous that sure elements of the face, together with the cheeks, decrease jaw and mouth, do appear extra inclined to environmental influences resembling weight loss program, getting older and local weather. However one other clue to that lacking issue, many researchers agree, lies throughout the distinctive genetics of particular person households.

Variants nice and small

If faces had been merely the sum of a whole bunch of tiny genetic results, because the GWAS outcomes indicate, then each youngster’s face ought to be an ideal mix, midway between its two mother and father, Hallgrímsson says, for a similar purpose that flipping a coin 300 occasions will virtually all the time yield roughly 150 heads. But you solely have to have a look at sure households to see that’s not the case. “My son has his grandmother’s nose,” says Hallgrímsson. “That must mean there are genetic variants that have large effects within families.”

But when some face genes do have large effects which can be seen throughout the households that carry them, why don’t they present up in a GWAS? Maybe the variants are too uncommon within the basic inhabitants. “Facial shape is really a combination of common and rare variation,” says Peter Claes, an imaging geneticist at KU Leuven in Belgium. As a potential instance, he factors to French actor Gérard Depardieu’s distinctive nostril. “You don’t know the genetics yet, but you feel this is a rare variant,” he says.

A number of different distinctive facial options that run in households, resembling dimples, cleft chins and unibrows, may be candidates for such uncommon, high-impact variants, says Stephen Richmond, an orthodontic researcher on the College of Cardiff, Wales, who research facial genetics. To search for such uncommon variants, although, researchers might want to transfer past GWASs to discover massive datasets of whole-genome sequences — a activity that must wait till such sequences, linked to facial measurements, develop into far more plentiful, says Claes.

One other risk is that the identical gene variants which have small results more often than not might have bigger results inside sure households. Hallgrímsson has seen this in mice: He and his colleagues, notably Christopher Percival, now at Stony Brook College, launched mutations that have an effect on craniofacial form into three inbred lineages of mice. They found that the three lineages ended up with quite different facial shapes. “The same mutation in a different strain of mice can have a different effect, sometimes even the opposite effect,” says Hallgrímsson.

If one thing comparable occurs in folks, it’s potential that inside a selected household — as with a selected pressure of mice — the household’s distinctive genetic background could make sure face form variants extra highly effective. However proving that this occurs in folks, with out the help of inbred strains, is more likely to be troublesome, Hallgrímsson says.

A greater method, Hallgrímsson thinks, could be to have a look at the developmental processes that underlie how faces are fashioned. Developmental processes contain groups of genes that work collectively — usually to manage the exercise of nonetheless different genes — to manage how particular organs and tissues kind throughout embryonic improvement. To determine processes linked to face form, Hallgrímsson and his crew first used fancy statistics to seek out genes that have an effect on craniofacial variation in over 1,100 mice. Then they turned to genetics databases to determine the developmental processes that every gene was part of. The evaluation flagged three processes as especially important: cartilage development, brain growth and bone formation. It’s potential, Hallgrímsson speculates, that particular person variations within the charge and timing of those three processes (and sure some others) could be an enormous a part of the reason for why one individual’s face differs from one other’s.

Intriguingly, it seems that a few of these groups of genes could have “captains” that direct the exercise of different crew members. Researchers attempting to grasp facial variation may thus be capable to concentrate on the motion of those captain genes fairly than a whole bunch of particular person genetic gamers. Help for this notion comes from an intriguing new research by Sahin Naqvi, a geneticist at Stanford College, and his colleagues.

Naqvi started with a paradox. He knew that almost all developmental processes are so finely tuned that even modest adjustments within the exercise of the genes regulating them could cause extreme developmental issues. However he additionally knew that small variations in these exact same genes are probably the rationale his personal face appears to be like completely different from his neighbor’s. How, Naqvi questioned, might each of those concepts be true?

To attempt to reconcile these two contradictory notions, Naqvi and his colleagues determined to concentrate on one regulatory gene, SOX9, which controls the exercise of many different genes concerned within the improvement of cartilage and different tissues. If an individual has just one working copy of SOX9, the result’s a craniofacial dysfunction known as Pierre Robin sequence, characterised by an underdeveloped decrease jaw and quite a few different issues.

Naqvi’s crew got down to scale back SOX9 exercise little by little and measure what impact that had on the genes it regulates. To take action, they genetically engineered human embryonic cells in order that they might dial down SOX9’s regulatory exercise at will. Then the researchers measured the effect of six different SOX9 levels on the activity of the other genes. Would the genes beneath SOX9’s management keep their exercise regardless of small adjustments in SOX9, thus conserving improvement steady, or would their exercise decline in proportion to adjustments in SOX9?

The genes fell into two courses, the crew discovered. Most of them didn’t change their exercise until SOX9 ranges fell to twenty % or much less of regular. That’s, they gave the impression to be buffered in opposition to even comparatively massive adjustments in SOX9. This buffering — presumably the results of different regulatory genes compensating for reductions in SOX9 — would assist hold improvement finely tuned.

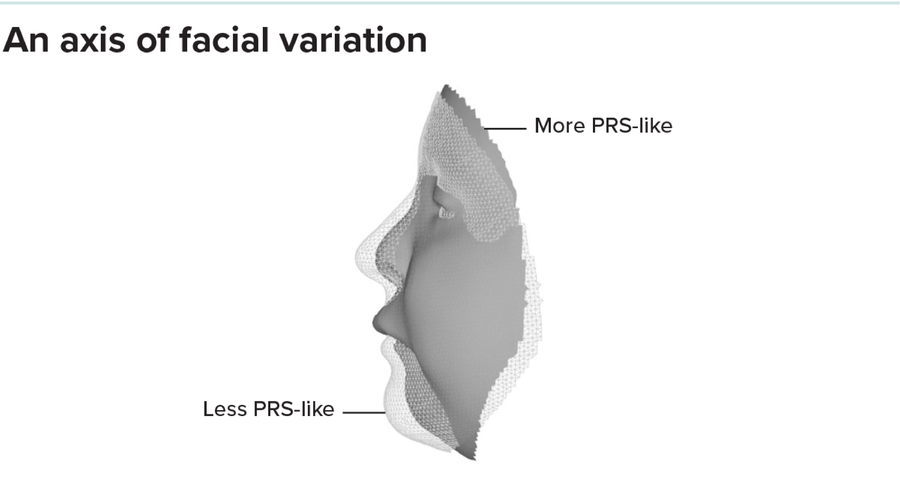

However a small subset of the genes turned out to be delicate to even small adjustments in SOX9, dialing their very own exercise up or down in lockstep with it. And people genes, the scientists discovered, tended to have an effect on jaw measurement and different facial options altered in Pierre Robin sequence. In truth, these unbuffered genes appear to find out how a lot, or how little, a daily face resembles a Pierre Robin one. At one finish of the vary lie the underdeveloped jaw and different structural adjustments of Pierre Robin sequence. And on the different finish? “You can think of the anti-Pierre Robin as an overdeveloped jaw, elongated with a prominent chin — kind of like me, actually,” says Naqvi.

In essence, SOX9 captains a crew of genes that outline one route, or axis, during which faces can differ: from extra to much less Pierre-Robin-like. Naqvi is now seeking to see whether or not different groups of genes, every captained by a distinct regulatory gene, outline further axes of variation. He suspects, for instance, that genes delicate to small adjustments in a gene known as PAX3 may outline an axis regarding the form of the nostril and brow, whereas these delicate to a different known as TWIST1 — which, when mutated, results in untimely fusing of the cranium bones — might outline an axis regarding how elongated the cranium and brow are.

Different proof hints that Naqvi could be heading in the right direction in considering that faces differ alongside predefined axes. For instance, geneticist Hanne Hoskens, Claes’s former pupil and now a postdoc in Hallgrímsson’s lab, sorted folks’s faces in keeping with how carefully they resembled the outstanding brow, flattened nostril and different options attribute of achondroplasia, the commonest type of dwarfism. (Consider the actor Peter Dinklage, for instance.) These on the extra dwarflike finish of the vary tended to have completely different variants of genes associated to cartilage improvement than these with much less dwarflike faces, she discovered.

If comparable patterns happen for different developmental pathways, this will set guardrails that prohibit the way in which faces develop. That might assist geneticists lower by way of the complexities to extract broader ideas underlying facial form. “There is a limited set of directions along which faces can vary,” says Hallgrímsson. “There are enough directions that there is a tremendous amount of variation, but it’s a small subset of the geometric possibilities we see. And it’s because these axes are determined by developmental processes, and there are relatively few developmental processes.”

Till extra outcomes are in, it’s too early to say whether or not this new method actually holds an necessary key to explaining why one individual’s face appears to be like completely different from one other’s — and the shock of recognition Eric Mueller skilled when he noticed his mom’s image for the primary time. But when Hallgrímsson, Naqvi and their colleagues are heading in the right direction, specializing in developmental pathways could provide a method to half the thicket of a whole bunch of genes that for thus lengthy has obscured our understanding of faces.

This text initially appeared in Knowable Magazine, an impartial journalistic endeavor from Annual Evaluations. Join the newsletter.